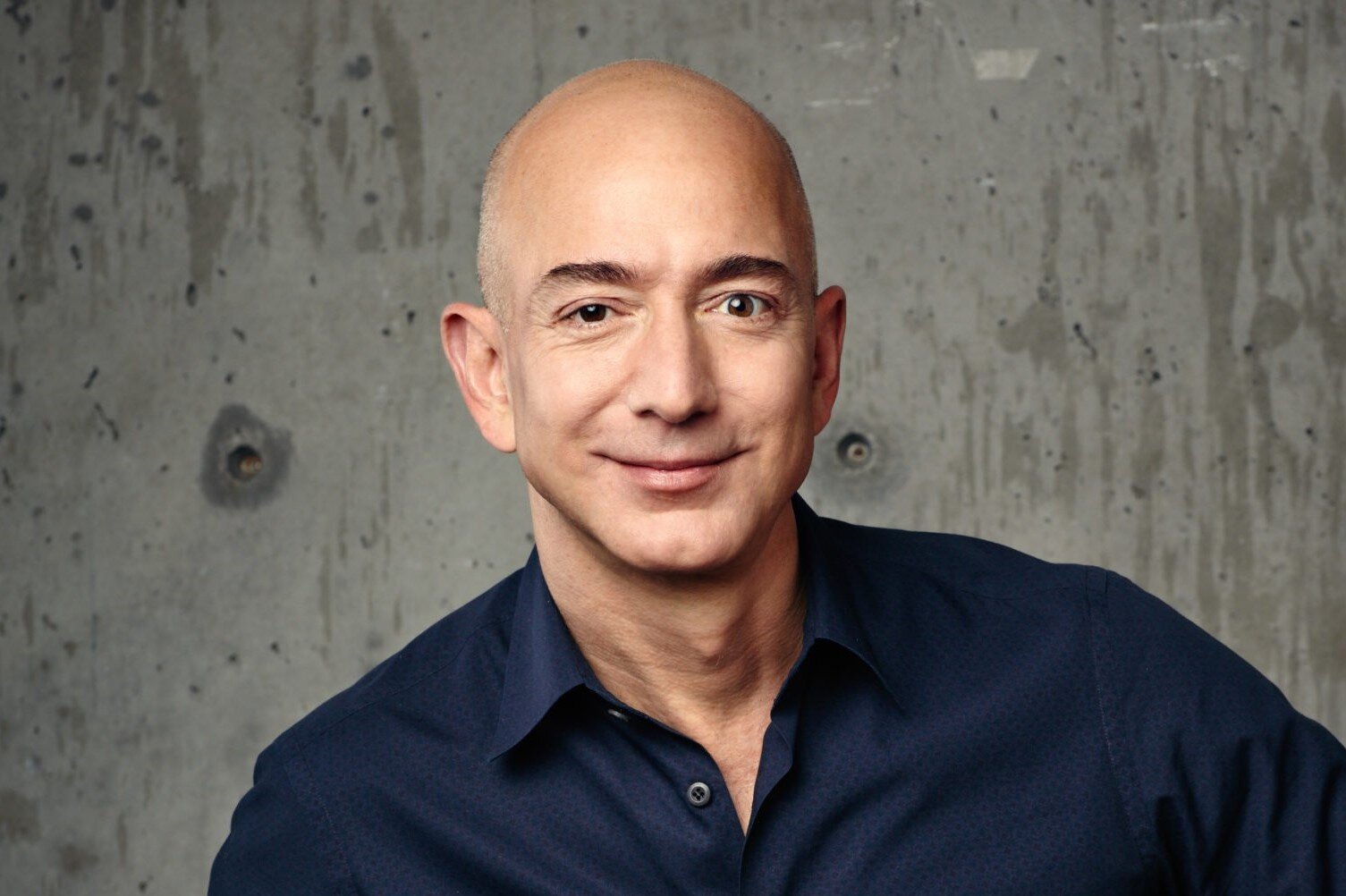

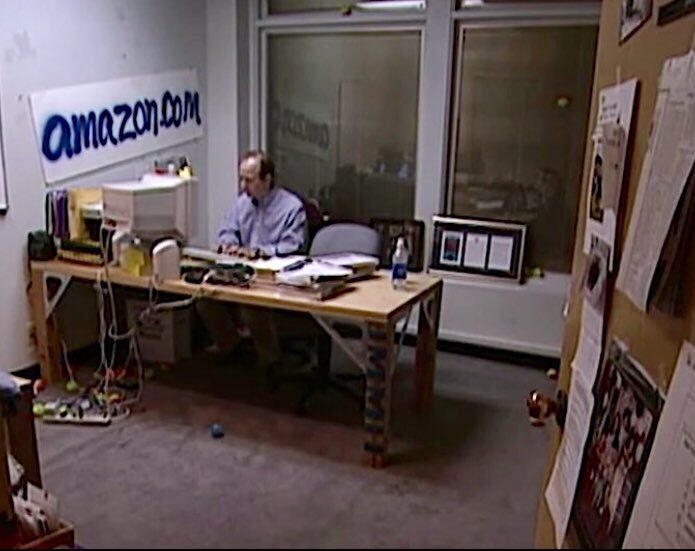

Jeff Bezos is constantly in the conversation for richest man in the world. In July of last year, Bezo’s net worth was estimated at $125 billion. That’s an insane amount of money. But Jeff Bezos wasn’t born with a silver spoon in his mouth. His mother was in high school when he was born and his father was a bike shop owner. Bezos built Amazon from the ground up into the E-commerce leviathan that it is today. The Amazon brand name is synonymous with quality, professionalism, and cutting-edge technology. Amazon’s competitors are few and share one thing in common: the instinct to imitate.

Money isn’t everything in life. That much is abundantly crystal to everyone who reads this blog. But without money you can’t eat, let alone take care of a family. I don’t often seek money advice, but when I do I want Jeff Bezos to be the guy giving it. I’ve transcribed a YouTube compilation in which Bezos reveals his tried-and-true keys to success. And his expressed definition of success is a lot broader than you might expect. It involves finding your passion and living with no regrets, even if it means sacrificing your bottom line.

Transcript:

You guys will find that you have passions, and having a passion is a gift. I think we all have passions. And you don’t get to choose them, they pick you. But you have to be alert to them, you have to be looking for them. And when you find your passion, it’s a fantastic gift for you because it gives you direction, it gives you purpose. You can have a job, you can have a career, and you can have a calling. And the best thing is to have a calling, and if you find your passion, you’ll have that. And all your work won’t feel like it to you. . .

Many many kids and many grown-ups do figure out over time what their passions are and sometimes we let our–I don’t think it’s that hard–I think what happens sometimes is we let our intellectual selves overrule those passions. And so that’s what needs to be guarded against. . .

One of my jobs as the leader of Amazon is to encourage people to be bold and people love to focus on things that aren’t yet working, and that’s good. It’s human nature. That kind of divine discontent can be very helpful. But it’s incredibly hard to get people to take bold bets, and you need to encourage that. And if you’re going to take bold bets, there are going to be experiments. And if there are experiments you don’t know ahead of time if they’re going to work. Experiments are by their very nature prone to failure. But a few big successes compensate for dozens and dozens of things that didn’t work. So bold bets AWS[Amazon Web Services], Kindle, Amazon Prime, our third-party seller business–all of those things are examples of bold bets that did work, and they pay for a lot of experiments.

I’ve made billions of dollars of failures at Amazon.com Literally billions of dollars of failures. You might remember pets.com or Kosmo–I could give myself a root canal with no anesthesia very easily. None of those things are fun. But they don’t matter. What really matters–companies that don’t continue to experiment, companies that don’t embrace failure, they eventually get in the desperate position where the only thing they can do is make a kind of Hail Mary bet at the very end of their corporate existence wheeas companies that are making bets all along, even big bets–but not bet-the-company bets. I don’t believe in bet-the-company bets. That’s when you’re desperate, that’s the last thing you can do. . .

You can be out of work and have terrible work-life balance, even though you’ve got all the time in the world, you could just feel like “Oh my God, I’m miserable.” And you would be draining energy, and so you have to find that harmony. And I think for most people it’s about meaning. People want to know that they’re doing something interesting and useful, and for us because of the challenges that we have chosen for ourselves, we get to work in the future. And it’s super fun to work in the future, for the right kind of person. . .

You need to be nimble and robust, so you need to be able to take a punch. And you also need to be quick and innovative and doing new things at a high speed. That’s the best defense against the future. And you have to always be leaning into the future. If you’re leaning away from the future, the future is going to win every time. Never ever ever lean away from the future. We all have adversity in our lives. I doubt if you know somebody, any friend, or anybody that you talk to. There’s no lack of adversity. By the way, that’s good because it’s what teaches us how to get back up. You fall down, you get back up. It always happens. You get certain gifts in life, and you want to take advantage of those.

My advice on adversity and success would be to be proud not of your gifts, but of your hard work and your choices. The kinds of gifts you get in life–you might be really good at math, it might be really easy for you. That’s a kind of gift. But practicing that math and taking it to the next step, that can be very challenging and hard. And take a lot of sweat. That’s a choice. You can’t really be proud of your gifts because they were given to you. You can be grateful for them and thankful for them, but your choices–you choose to work hard. You choose to do hard things. Those are choices that you can be proud of. . .

Being an inventor requires because the world is so complicated–you have to be a domain expert. Even if you’re not at the beginning, you have to learn learn learn learn enough so that you become a domain expert. But the danger is once you’ve become a domain expert, you can be trapped by that knowledge. And so inventors have this paradoxical ability to have that 10,000 hours of practice and be a real domain expert AND have that beginner’s mind. Have that [ability to] look at it freshly even though they know so much about the domain. And that’s the key to inventing. You have to have both. And I think that is intentional. I think all of us have that inside of us, and we can all do it. But you have to be intentional about it. You have to say “I am going to become an expert, and I’m going to keep my beginner’s mind” . . .

You can’t skip steps, you have to put one foot in front of the other. Things take time. There are no shortcuts. But you want to do those steps with passion and ferocity. . .

It’s easy to have ideas. It’s very hard to turn an idea into a successful product. There are a lot of steps in between, and it takes persistence, relentlessness. So I always tell people who think they want to be entrepreneurs–you need a combination of stubborn relentlessness and flexibility. And you have to know when to be which. Basically you need to be stubborn on your vision because otherwise it will be too easy to give up, but you need to be very flexible on the details because as you go along pursuing your vision you’ll find that some of your preconceptions were wrong. And you’re going to need to be able to change those things. So I think taking an idea successfully all the way to the market and turning it into a real product that people care about and that really improves people’s lives is a lot of hard work. . .

Don’t try to chase what is kind of the hot passion of the day. I think we actually saw this–you see it all over the place in many different contexts. But I think we saw it in the internet world quite a bit where the peak of the internet mania in say 1999. We found people who were very passionate. They kind of left that job and decided I’m going to do something in the internet because it was almost like the 1849 gold rush. You find that people–if you go back and study the history of the 1849 gold rush–you find that at that time everybody who was within a shouting distance of California–they might have been a doctor but they quit being a doctor and started panning for gold. And that almost never works, and even if it does work according to some metric–financial success or whatever it might be–I suspect it leaves you ultimately unsatisfied.

So you really need to be very clear with yourself and I think one of the best ways to do that is this notion of projecting yourself forward to age 80 looking back on your life and trying to make sure you’ve minimized the number of regrets you had. That works for career decisions. It works for family decisions. I have a 14-month old son and it’s very easy for me to–if I think about myself when I’m 80, I know I want to watch that little guy grow up. I don’t want to be 80 and think “Shoot, I missed that whole thing, and I don’t have the kind of relationship with my son I wished I had.” And so on and so on. So if you think about that.

I guess another thing I would recommend to people is that they always take a long term point of view. I think this is something about which there’s a lot of controversy. There’s a lot of people, and I’m just not one of them, believe that you should live for the now. I think what you do is you think about the great expanse of time ahead of you and try to make sure that you’re planning for that in a way that’s going to leave you ultimately satisfied. This is the way it works for me. Everybody needs to find that for themself. I think there are a lot of paths to satisfaction. And you need to find one that works for you.

[…] 参考 : Keys to Success (Jeff Bezos) […]