There are few things as foundational to a good life as security. Many political scientists have argued, in fact, that that the drive to achieve greater security has been the chief engine of political and economic development throughout human history. This same impulse has motivated countless innovations, spurred massive economic growth, and led to the consolidation of bigger and more elaborate forms of political organization. From the hunter-gatherer tribe, to alliances of small political states, to behemoth modern nation-states backed by high-tech militaries, how people collectively define and achieve security has expanded and evolved dramatically in time. Today, the US military is the most sophisticated and powerful fighting force in the world, and the manner in which war is waged continues to evolve at a fast clip.

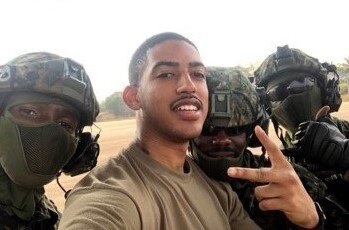

This week I brought in my friend and former teammate, Trenton Dennis, to shed light on his experiences as an Airman in the US military. Fresh out of high school in 2015, Trent enlisted in the Air Force as an Airman Basic before earning promotions to Airman First Class (2016), Senior Airman (2018), and to his current role as Staff Sergeant as a non-commissioned officer (2020). Trent’s experiences have taken him all around the world, from Texas to Tokyo to Little Rock, Arkansas, where he trained for his eventual 6-month deployment to Kabul, Afghanistan.

In September of this year, Trent will have fulfilled his 6-year commitment to the US military. I hope you find Trent’s reflections—taken from a live 90-minute interview this week—as candid and insightful as I did, both as it relates to his life, in particular, and to life in the American military more broadly. You can catch Trent on Instagram @vii_ii_xcvi

Tell the people a little bit about yourself.

My name is Trenton. I’ll be 25 years-old in July. I was born and raised in Columbus, Ohio. I grew up with my little sister, older brother, and both of my parents. I became interested in soccer at a young age. Soccer was a big thing for me, especially in high school. It’s how I met you and most of my friends today. About a year after barely graduating high school, I decided to enlist in the Air Force.

What was so hard about school?

I was doing all right in school up until about the 8th grade and freshman year, but it got to a point where I was really not interested in any of the work–I was not a good student. School felt like a chore they made us do, while I put a lot of my energy into soccer, which was my true passion. I did not see any value in school at the time, although I feel differently about it now that I’m older.

There are various reasons people join the military—career benefits, personal growth, national pride—what was your motivation?

I guess the answer for me was career growth. After high school, I originally thought about going to college just because that’s what the normal, usual next step is. My dad brought up the obvious fact that I’m not really school-oriented, and I agreed with him. He told me that I should think about doing something else. He mentioned the military, which wasn’t even on my mind at the time.

I didn’t want to go to college, but I didn’t want to be a bum, either. I didn’t want to get a minimum wage job and just sit around. I wanted to do something and make something of myself, so I started looking into the Air Force. The Air Force to me looked like a whole other world where you get to travel, wear a uniform, and learn a job. It seemed new and stimulating, and I was interested. For some people, the main motivation is to serve our country and something like that, but for me it seemed like the best career path for my life.

I graduated high school in 2014 and enlisted in September of 2015. I would have enlisted sooner but they were trying to limit enrollment at the time. I had to wait 3 or 4 months from the time I talked to a recruiter and committed before I could officially get started.

How did your path in the military evolve?

The first determining factor is whether you’re enlisting or commissioning. Enlistment is for people who do not have a bachelor’s degree. Enlisted service members make up more the worker-bee tier of the military. Commissioning is for people with degrees that the Air Force accepts. Commissioned officers serve in an administrative/leadership capacity. They manage people from the get-go and deal with bigger scopes of the mission. Entering straight from high school, I started off on the enlisted track.

The first main goal of basic training is to teach you how to focus, to teach you how to control your emotions, and to teach you how to think under stress. Something as simple as controlling the movement of your body. Being able to speak, for example, without moving your hands. I think these are all good skills for people to learn, especially at a young age. Over time, they do a good job of incorporating more responsibilities. Ultimately, it’s on you to step up and accept those responsibilities.

When I finished basic training, like many people starting out, I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do. I decided to start training to be an Explosives Ordinance Disposal [EOD] Technician. Basically, a bomb de-fuser for the military, like in the movie The Hurt Locker, except in real life. EOD is a difficult job and requires a lot of training. The preliminary training was broken down into 5 weeks, with a separate focus each week. It was a 2-strike and your out system. We had tests every 3 or 4 days. Some of the tests were written, others covered more hands-on type stuff. If you failed one, you got a chance to retry it the next day. If you failed again, that’s two strikes and you’ve washed out.

I can’t disclose details, but I failed a written test during the first week. That was strike one. I made it through the rest of the training until the very last test, week 5. It was a simulation. I failed that test, as well. Strike two—I had washed out.

By the end, there were only 4 people who graduated out of the 25-30 people who started. I would have been the 5th. The graduation was going to be that same day. In fact, I had brought my service uniform with me that I was supposed to graduate in, and had too take it back with me on the bus back to the dorm. I came really close and washed out on the last day.

What was going through your mind in that moment?

It was very upsetting at first. I had failed a test I tried very hard to pass. But then it was relief, for sure, because it was very stressful. The whole training was very intense, and I was also still trying to decide if this was something I really wanted to do or if I was just doing it for the stimulation.

It’s one of those jobs you have to really be passionate about. There were days when I didn’t really want to be there, but I kept going because I signed up for it and didn’t want to be a quitter. In the end, I was very relieved that I got do all of that and move forward with something else. If I had passed, I would have had to go through another year of that type of training.

What happens after you wash out?

The military places people who don’t have a job wherever they deem fit. I didn’t choose my next assignment as an engine mechanic—engine troop, as we call it—but that’s where they placed me. Engine mechanic has been my first and only job with the military. Obviously, the responsibilities changed and increased over time. At first, you learn about the different parts of the engine and later they trust you to work more efficiently by yourself. Once I earned the rank of Staff Sergeant, it was a lot less hands on, more just watching, but still in the same line of work.

How do promotions in the Airforce Work?

Everyone starts off with the rank of Airman Basic. After basic training, you gain stripes based on how many years you decide to enlist. I decided to enlist for 6 years instead of 4, and so I was eligible for two stripes after a few months, at which point I became an Airman First Class. I later got my third stripe and was promoted to Senior Airman. About a year after that, I passed the test to become a Staff Sergeant as a NCO [non-commissioned officer]. I have been a Staff Sergeant for a year and 5 months now. The test consisted of technical stuff about the job, Air Force history, and an enlisted performance report. This was my first supervisory role and gave me good leadership experience. I had to deal with both work-related and personal issues in the lives of people I managed.

Obviously, the higher up you go, the fewer people get promoted. I would guess that around 30 to 40% of people get promoted to NCO, maybe 20 to 30% to Technical Sergeant, and a lot fewer for Master, Senior Master, and Chief Master Sergeant.

Describe your various stations and how you ended up being deployed to Kabul.

My first stop was San Antonio, Texas, where basic training takes place for everyone in the Air Force. This is where they yell at you and teach you how to control yourself.

My second stop was Wichita Falls, Northern Texas. That’s where my training for EOD Technician and engine mechanic took place. That’s probably why they had me work as an engine mechanic–for logistical reasons–since I was already there.

There is where I was informed that the first base where I would be serving as an engine mechanic would be in Tokyo, Japan. It was a two-year time frame. At that time, I was an Airman First Class and got promoted in Tokyo to Senior Airman.

My next stop was in Little Rock, Arkansas. This one was for three years. Different bases have different missions and goals. In Japan, they’re not a part of deployment efforts. People go there for training and things like humanitarian missions. In Arkansas, the mission was to support the war effort, and so people there rotate in and out of deployments very often.

My first deployment out of Arkansas was to Afghanistan. I didn’t know what to expect. A lot of my Staff Sergeants made it sound like a good time, hanging out, focusing on work–without having to deal with politics or anything crazy like that. It sounded pretty scary at the time of deployment, but we were pretty safe for the most part.

I served in Afghanistan for 5 months. It was a lot of work, and we were there during the winter months. Afghanistan gets cold in the winter, especially at night, if anyone didn’t know. I think there was one week where we got about a foot of snow. Overall, it was a lot of work, and a rough time, but I made a little extra money. You get extra incentive pay when you get deployed. You get hazard pay. You get family separation pay. And they don’t take any taxes from your paycheck, so you’re not paying taxes during that time. There’s also nothing really to spend money on while you’re there, so you end up saving a lot more, too.

Did you face any security concerns while you were there?

The base was obviously located in the midst of a war. There were definitely people around the base who didn’t want us there. As engine mechanics, we were not given that much information on who’s doing what and for what reasons. That’s more the intel side. Randomly, on certain days, we would get strikes coming from off base. Nothing too crazy. Usually, the base would deal with them no problem, as the base was built to defend against those kinds of attacks. The system wasn’t perfect though, and sometimes the strikes would land somewhere on the base.

To my understanding, these were smaller mortar-sized artillery. The assailants didn’t use too much technology or strategies, they were kind of just shooting blindly at the base. Whenever there was an attack, an alarm would go off and you would have to lie down and take cover. They would notify us via a robotic pre-recorded voice when something was incoming, when impact happened, and when it was safe to come out. After that, we’d sweep our area for damage, or potential damage, before the “all-clear” sign was given. This event probably happened 16-19 times during the 6 months I was there.

Is deployment to a war zone ever optional?

No. This is something you sign up for when you join the military. You go where they tell you unless you have a really good reason not to, like physical illness, single parent status, or a death in the immediate family.

I actually wanted to deploy again. Back in Little Rock, they moved me to a new squadron with a different objective. I went from a mission-oriented squadron that supported deployments to a training squadron where I repaired aircrafts for student trainees. It was a slower tempo environment that I found a lot less stimulating. This switch was actually a factor in my decision to rejoin civilian life.

If you had another go at the last 6 years, what is one thing you would do differently?

I’m pretty satisfied with the last 6 years and everything that happened. I definitely would have joined the military again. I definitely wouldn’t have went straight to school. Instead of signing a 6-year contract, I could have signed a 4-year contract. Not that I would have left earlier, but it would have given me more flexibility. As far as a job, I could have waited more for them to give me a job that I wanted to do instead of starting right away on the EOD track and getting assigned to be an engine mechanic. However, this experience, both in EOD training and as an engine mechanic, made me a lot more handy and taught me how to be mechanically inclined. Overall, I have no regrets.

How do you think the military is different today than it was in the past?

The Air Force is more professional, less rugged, more diverse, more understanding, and more open-minded than how I understand it to have been in the past. The environment, for the most part, is similar to what you might experience at a normal civilian corporate job. When you think of military, you may think of wars and yelling and ruggedness—not professional—and I imagine it was more like that the further you go back in time.

What about the future?

It seems like things are going more in that direction, which is interesting to me because I do feel that the military needs to keep a little bit of that ruggedness. A professional and corporate environment doesn’t work for everyone. Having that edginess, saying what you feel, and being yourself a little more in the military can be a good thing. But there are officers who do a whole lot of research and know wat more about it than I do.

I think this is happening more in the Air Force due to the technical type of jobs where that traditional military culture isn’t really necessary. The Air Force is isolated, for the most part, from the ugly part of war. The army and the marines is a different story.

What is something people don’t know about the military?

For one, there are separate branches. People refer to me as a soldier as if I were in the Army all the time. The Air Force is not the Army. The Army is not the Marines. It’s all the military, but the culture, the uniforms, the names of the ranks, basic training—literally everything is different. It’s similar to different colleges. You’re all going to school to learn something, but the environment and the teachers are different.

The Air Force is not as traditionally military as people might think. It’s a lot like a regular job, except we wear uniforms, the standards are higher, and things are a little more strict. Once you complete basic training, of course, where you get all the alarms, the shooting, and the running in groups.

What is the biggest life lesson you’ve learned?

I’ve learned plenty of lessons, although I don’t know what the biggest one is. One thing the military taught me is that how you present yourself—how confident you come across to other people—is definitely important. Especially in my career field, where it’s high risk. I literally maintain the engines of aircrafts that are going to be flown by people in the middle of war zones. The way you look and how confidently you speak about what you’re doing is is very important to earn people’s trust.

Also, you have to learn how to figure things out. A lot of people are quick to give up when they come across obstacles. They think it’s too hard and that’s the end of it, but this is an important lesson I learned in the military. Obstacles are going to come up, but you have to figure out how to get through them.

What is the thing you are most proud of about your service?

No one in my immediate family had every been in the military, so this was all new to me and out of the ordinary. And I knew I would have to leave my friends and family. Similar to most people when they first join, I didn’t really know what to expect, besides what I saw on TV about basic training and what have you.

I was 19 when I joined—basically a kid—and I still thought like a kid. During the last 6 years, I grew and matured and gained a lot of experience. I’m proud of my decision to join, and I’m proud of who I’ve become.

What do you think it would take to achieve world peace?

I don’t know how to answer that question. But in a joking way, and also kind of serious, we need a common enemy. If another planet came to invade, or something like that, and we all had to come together to defend earth—that’s the only way I can see that happening. As it stands, there are too many different people, too many different cultures, too many different ideals. We would need a threat so big to distract us from all our differences and to realize that the things we’re fighting over are ridiculous.

What’s next for you?

I’ll be finished with my military service in September of this year. I’m currently home early in Columbus, Ohio, due to a program the Air Force has that helps you transition back to civilian life. I’m working on the military’s dime at a warehouse for an E-commerce company. In September, the company has the choice to hire me in an official capacity.

My next big goal is going to college next spring, hopefully full time at The Ohio State University. I still need to figure out what I want to major in. I’m also looking to invest in some rental properties. I have a friend in real estate who’s helping me see if I can find something worth purchasing in this red hot market.

Thanks so much for this inspiring article with Trenton. Needless to say we are very proud of him!!! Proud Parents