Any year the word “pandemic” is among the most popular search terms in Google, you know you’re in for a ride. If you’re like most people, the word itself is synonymous with some special challenge or circumstance you’ve had to endure. Many people have gotten sick. Many people have died. And an even great number have been compelled to make unwanted lifestyles changes. I have a few friends who entered the year physically and mentally unscathed, but they are the exception to the rule. The rule is that pandemics suck, and it takes special coping skills to make it out on top.

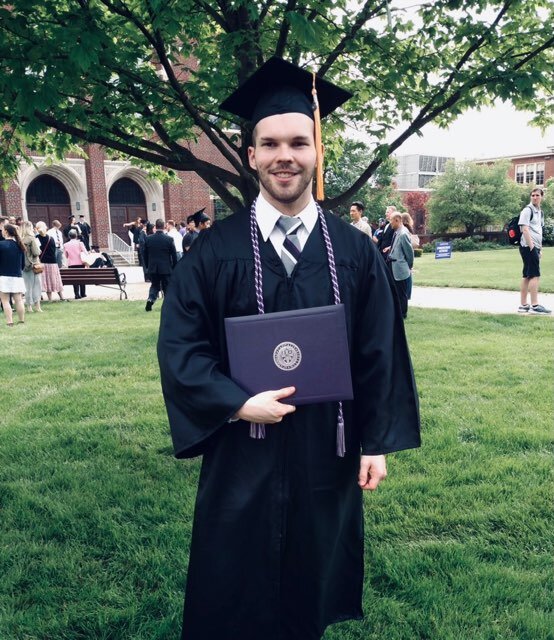

This week, I brought in my guy and newlywed, Chase Ridgway, to serenade us with his wisdom on the theme. Chase is the ultimate insider. He graduated from Capital University in Columbus, Ohio, with his Bachelor’s degree in Nursing. Chase worked in a pressure cooker environment for four years in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit [ICU] at Ohio State Wexner. Chase also recently spent a few months on assignment to a unit that treated a number of Covid 19-positive patients. Due to his background and even-tempered personality, our interviewee is uniquely qualified to address the topic of stress management amidst a global pandemic. Never at a loss for words, I hope you find Chase’s experiences and reflections, taken from a 90-minute in-person interview, to be exquisitely practical, eye-opening, and down-to earth. FYI, I defined a few medical terms in brackets to save you time and give your thumb a break from all that scrolling.

Tell the people about yourself.

My name is Chase Ridgway. I’ve been a nurse for five years. I spent my first four years in the ICU before transitioning over to endoscopy [procedures to look inside the body’s digestive system]. I am also currently taking classes to become a Family Nurse Practitioner.

As far as my personal life goes, I am recently married and the proud father of a black and white greyhound named Franny, and two black cats, Arnold and Mena. In my free time, I like woodworking, lifting weights, yoga, biking, boxing, and frequently hiking with my wife and family. I try to maintain an active lifestyle to stay healthy first and foremost, and to make sure what I preach and what I practice are one and the same.

What informed your interest in the medical field?

It was a family thing. My sister, my cousin, and my aunts were nurses. They liked their jobs. I’m also a people person. I knew I wanted to do something that involved people. Nursing is also a pretty steady occupation. You are never going to run out of people to treat. In fact, the healthcare profession is actually gaining patients.

I was also a heavy kid growing up. I had a really cool pediatrician, Dr. Heiny, who helped me get on the right path. Dr. Heiny didn’t ignore me and talk to my parents. He was very personable, very friendly, and talked to me on my level. He was also very upfront with me about losing weight, and told me very plainly in middle school that I was prediabetic, and without lifestyle changes, I could develop type-2 diabetes. To help combat this eventuality, Dr. Heiny made getting healthy into a point system and a game. He had me participate me in Weight Watchers and count the calories of everything that went into my body. He also suggested trying out sports to see what I liked. This led me to volunteer to play football in middle school, which along with many years of baseball, helped me trim down about 90 lbs from my freshman to senior year of high school. My background explains part of my interest in bariatric care [management of obesity] to this day.

How did you start out working in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit? Was your temperament a factor in the decision?

I knew it is what I wanted to do straight out of college. I thought the intense stuff would be the most interesting, and I thought it would give me the opportunity to help the largest number of people. In reality, it was mostly about managing preventable conditions. A lot of people were chronically ill. Some had done permanent damage to their bodies. I watched the health of a lot of our patients deteriorate. This led me to want to shift to primary care to focus on the prevention side. People in hospitals often need band-aid care. We fix them up so they can return home and go about their lives. As a Nurse Practitioner, I want to help fight health issues before they develop and prevent these terrible conditions that people get admitted to the ICU for. It starts early, by being proactive and with the proper education.

I am generally a calm guy, but the stress of the ICU will take its toll on anyone. There were a lot of sad cases of drug abuse and overdose that were very difficult to manage. We also had cases where a single sick patient might have 10-12 different medications running through their IVs. Family members would often ask questions that nobody could be sure of. And about once a month, one of my patients would pass away. I was also working nights. I would typically work 7 PM to 7 AM, several days a week, and pick up a lot of overtime. On days I worked, I would sleep from 9 AM to 4 PM. I barely saw anyone, and when I did see someone, I would lose sleep. Whenever I had several days off in row, I would typically sacrifice two of them just flipping back to a normal sleep schedule.

My first few months in ICU were rough. I had a hard time going to sleep, thinking of everything that happened that day and playing out different scenarios in my head to make sure I was prepared. I got better at stress management over time, but it’s something you have to constantly stay on top of in that environment. ICU was intense, and it was fun. I liked it, and I learned a lot, but I knew it wasn’t something I could continue for life. Around year three, I could sense that it was time for a change.

What’s the most chaotic situation you’ve ever had to deal with?

We once had a patient who had just suffered a heart attack. He was in cardiac arrest and came to our catheter lab to receive treatment. By that time, he had already been unresponsive for a couple hours. His blood pressure was very low and his organs were starting to shut down, and began doing CPR and giving meds. It was basically I and a few nurses running a code [trying to save a dying person], and we were fortunately able to get him back. The patient had a bunch of occlusions in his heart and was admitted from the cath lab to the ICU floor. He had like 20 family members with him, and they all wanted answers. They stayed up all night in the waiting room because they didn’t know if he would make it to the next morning.

The patient wasn’t showing any signs of life neurologically. His lab values from his blood showed massive organ breakdown and death. His family was camped out, praying, hoping for the best. They wanted to wait until his daughter could come see him before he passed. And so we spent the whole night trying to keep him alive long enough for his daughter to say goodbye. As for the doctor, he was sitting outside his room the entire time, ordering meds and directing us what to do. The patient’s electrolytes would get out of whack, and we’d have to correct it or he would go into cardiac arrest again. He needed blood drawn every hour and meds every 20 to 30 minutes. He had 5 or 6 IV drips going. Three of them are called vasopressors to help keep his blood pressure high enough.

It was a chaotic situation. I would go out and talk with the whole family as often as I could, every 2 or 3 hours, to give them updates. One thing they talk about is not giving false hope but remaining positive, which is not easy to do. It’s hard to tell the truth and be honest about his condition and not inspire false hope. “He’s still fighting, and he’s not doing any better.” You try to ride the line and be as respectful as you can.

The man wasn’t in good shape, but he made it through my shift. We stabilized him long enough so his daughter could some see him the next day. When I came back the next night, he was gone. The family decided to reverse his code to DNR [do not resuscitate], and turned off all the medication. It was a tough situation for everyone. I’ve had a lot of patients in critical care, but he was one of the most difficult to keep alive, and one of the most emotionally taxing to take care of.

How do you stay calm under pressure? Is there a special motto or breathing technique or prayer or meditation that you resort to?

I’ve always been a guy who doesn’t overreact to things. Some of it is built into my personality. I can’t say that I have a special secret or mantra, but I have learned from working in ICU that work stress isn’t worth bringing home. Don’t worry about anything you can’t control. I don’t think about it or dwell on it. At the end of the day, it’s a choice. I know it’s not always easy to do, but knowing that is what makes the difference for me.

My calmness also comes from being sure that I am in the right place doing the right thing with my life and that I have the right knowledge to help. I gave it my all in my schooling and in my training and I felt like as long as I kept learning and getting better, I could remain calm in every situation. Listen to those who know best in an area, and you can feel confident enough about what you’re doing to experience that same effect. Knowledge is key here, as is the ability to keep learning and listening.

I’ll add that physical activity is the number one way for me to de-stress in the moment. Early in my career, like I said, I was very stressed out. During the first few months, I’d be so keyed up from work that I would come home and work myself out to exhaustion and hope to be able to fall asleep after that. I would get home at 7 AM and wouldn’t go to bed until 1 PM, because I was so focused trying to remember everything and make sure I did the very best I could. I eventually got better at the work-life balance, but it wasn’t always easy.

Music is another big one. I rarely ever drive in complete silence. Music and comedy, but between the three, physical activity for me is king. They were also pretty big on deep breathing in my undergraduate program. Whenever you can, take a moment to deep breath, focus, and try to process as much stressful input as you can.

Based on your reflections, it sounds like there is a lot of grace built into our biology. In a word, physical and emotional health is capable of changing for the better.

Health outcomes can always be improved with diet, exercise, and stress management. Even in cases where permanent damage has taken place, lifestyle changes can help prevent the situation from getting worse. Take diabetes, for example. The pancreas is no longer able to secrete its own insulin after irreversible damage has occurred. However, diabetics who make lifestyle changes will likely need less insulin, lose weight, and generally feel better. Immune function may go up. Fatigue may go down. It’s not a cure all, but it makes a huge difference. And that is a kind of grace.

Hypertension [high blood pressure] is another example. Depending on the cause, hypertension can be reversible. Salt intake. Fat intake. Caffein intake. Weight. Stress. And some people also have other conditions that influence it and need managed. You should always first develop a plan of treatment with your doctor, but generally anyone can improve their health at least a small amount with lifestyle changes. The goal is to get your body working better, feeling better, and hopefully living longer.

The sicker and more out of shape you get, the harder it becomes to reverse health outcomes. If you’re immobile, for example, or if you’re very old. It is always best to make lifestyle changes as soon as you can wherever you are.

How has the pandemic influenced the healthcare industry, in general, and your occupation, in particular?

Healthcare has become a lot more careful about what visitors they let in and who is being treated where. They’re a lot more careful about making sure employees call off when they’re sick. I know a lot of nurses who are workaholics and would come in no matter what. With Covid, they realize their health can deteriorate if they put extra stress on themselves, and they also run the risk of getting their coworkers and patients sick.

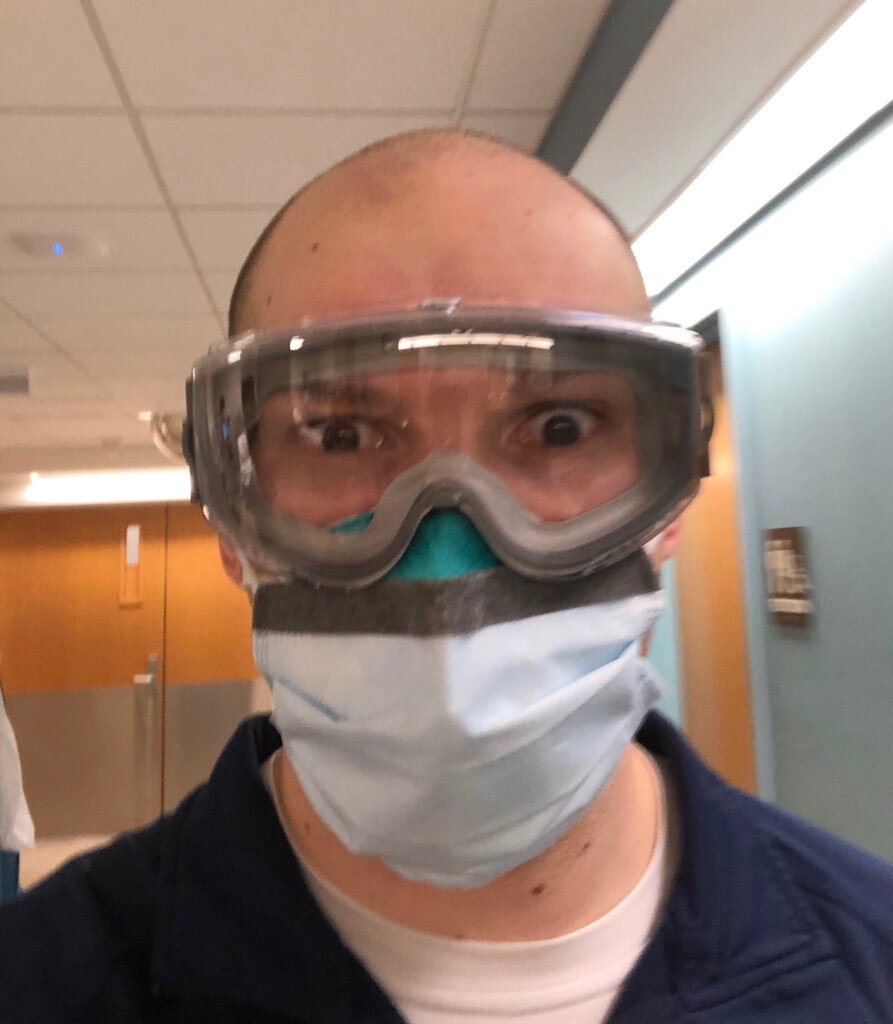

I also see a lot more people doing touch point cleaning in and around our work stations. As a nurse, we wear a lot more PPE [personal protective equipment]. Masks. Gloves. Eye shields. For example, we all wear N-95s or respirators whenever administering an upper endoscopy to patients. These tests look for infections, inflammation, ulcers, genetic diseases, things like that. And we have all our patients get tested for Covid before entering our unit.

You recently got assigned to a unit that saw a number of Covid-19 patients. What was it like working in that environment?

It was an in-patient Covid overflow unit. About fourteen of us from endoscopy received this assignment. The unit was created because Covid cases were rising and they were trying to isolate Covid patients on the units these people came from. It was difficult for everyone. I was gone from in-patient nursing [overnight care] for about a year, and some had been gone even longer. And so we were all worried about patient safety and making sure we were back to being competent and patients were getting appropriate care. It was dicey at first. I oriented for about two weeks, and there was the option to orient for even longer for those who needed it.

We took care of patients who had tested negative and others who ended up testing positive. It was a brain and spinal hospital, so a lot of people had neurological issues. Some patients had liver disease and some were there for surgeries. Time management was the biggest thing. It’s a skill that often gets lost in the moment. In endoscopy, we would hyper focus on one patient whereas on this unit were taking care of 3 or 4 patients at a time and needed to divide that time adequately to care for each patient. In this way, it resembled the ICU.

A few weeks ago you received a vaccine. How did that go?

Healthcare workers were one of the first populations to get offered the vaccine. It wasn’t required, and some were hesitant, but most went ahead and got it. A few weeks ago, I got my second dose of the Moderna vaccine, which consisted of two shots four weeks apart from each other. My only symptom after the first shot was a sore arm. It felt just like a flu shot. People who had got it before me said the second one was pretty rough, at least rougher than the first. After my second shot, I felt very fatigued. I had body aches and nausea. Not everyone experiences these symptoms. They say two thirds of all people don’t feel anything beyond a sore arm.

To my mind, it’s well worth it. If you do contract the virus, there’s a less likelihood of developing severe symptoms. However, it’s still unclear if you can spread it after you get the vaccine. People still need to be careful, wear masks, and take all the other precautions.

What’s the most challenging part of working in healthcare?

It’s very physically exhausting. You’re constantly in motion, gathering resources, going from room to room to take care of different patients. It’s not an easy job. Some patients are less appreciative of your help than others, which can be frustrating.

What about the most rewarding?

Making a positive impact in the lives of others. Helping people get home and live healthier lives and hopefully not have to come see us again. The job can be demanding, the job can be stressful, but I know the work we do is meaningful. And, in spite of everything, there have been very few days where I didn’t feel like going in.

How does your current job in endoscopy compare to working in the ICU and the Covid Unit?

Endoscopy is all out-patient, so people generally go home the same day. There are 30-40 employees on any given day, and we see anywhere from 60-80 patients in a day. It’s a very high-functioning environment, and we get each patient in and out of the hospital within a couple hours. Each procedure lasts anywhere from 15 minutes to an hour or more, and they take place in any one of 9 procedure rooms. I prefer endoscopy not because it’s low pressure but because we deal with one patient at a time. This allows us to get know that individual a little bit and fully focus on what we’re doing. We also have a good camaraderie among the staff, as we take care of the same patient in different phases. There are also fewer life or death situations, and so that helps with the stress. The biggest difference I find is I’m physically but not mentally exhausted at the end of the day.

The flexibility is one of the things I appreciate the most about nursing. There’s opportunity to try something new if you get bored or unhappy where you’re at, no matter where that may be.

You’re currently in school. Tell us more about the endgame you have in mind.

My end goal is to become a Family Nurse Practitioner. FNPs can prescribe medication, examine patients, diagnose and treat conditions, whether that be with medication or other kinds of interventions. A typical visit covers a lot of what you would have done during a normal doctor’s appointment. Eventually I’d like to specialize in bariatric care, preferably with kids, or diabetes, or maybe become a general practitioner who sees patients of all different kinds in an out-patient setting. I’ve got about a year and a couple months left of the 3-year program. OSU Wexner has a full-time work, part-time study program where they offer tuition assistance.

I’m currently taking around 9 credits. We’re learning assessment techniques and pharmacology, where you learn about all the different drugs to prescribe and their various contraindications [reasons not to prescribe a medication]. It can be stressful to work full time and do school, but I feel like with the time management and study skills I’ve acquired, it hasn’t been as bad as I thought it would be.

Your wife is also a nurse. How has being married to someone in the same field influenced your life?

I think being married to someone in the same field makes it easier to destress, especially for people with stressful occupations. Megan works with cardiac patients at Nationwide in the ICU, and I’ve already said a lot about the challenges of working in that environment. It helps to connect with someone of similar interests or work because you have shared experiences, and communication become that much easier.

Healthcare, in general, is a specialized thing where there is a lot of intimacy between patients and coworkers and everyone involved because it’s the work of improving lives and providing the best possible care. Healthcare is a lot different from other fields. There’s a very real healthcare community, and it helps to have someone who is a part of that and can relate to that. When my wife and I first met, we were both on the night shift, which helped us connect and made it a lot easier on our relationship. Megan is currently studying to be a CRNA [certified registered nurse anesthetist], and so were both doing the work-study thing and can relate to each other’s experiences in a big way.

What advice would you give someone who came to you for help with stress management and emotional control?

The key is to take a minute and think about all the resources you have, whether that’s knowledge, giftings, skills, or people. My ability to stay calm and in control, in my relationships, work, and the goals I’m working toward, is about having confidence in those resources. It’s also important to have good coping skills to destress, and to find activities or hobbies that have a relaxing effect on the mind. Stress management, like good health, is all about prevention. You don’t want to wait until you’re in an emotional crisis to act. You want to take steps now to set yourself up for success in the future.

Boundaries are also important. Don’t pull yourself in too many directions. Don’t get too emotionally involved with your work. Don’t take things personally. And don’t dwell on negative experiences. I know that’s easier said than done, but it’s a skill that can be developed. I made the choice to sacrifice social time, and time spent on hobbies, to dedicate to being a full-time nurse and student. My lifestyle works for me, but everyone should weigh their emotional health and well-being before taking on any new commitments. Think about the sacrifice that will be involved and whether you will be able to follow through. And remember, you can still be happy while you make sacrifices to pursue your goals and ambitions.

They say success in nursing is as much about taking care of yourself as it is taking care of patients. The same applies to other areas of life. Self-care is important because it affects your outlook on life, how others see you, how you see yourself, and how you interact with the people around you. If you’re not allowing yourself time and space to decompress and relax, whatever that looks like for you, then you’re setting yourself up for failure.

You have the last word.

Wear your masks. Stay away from people when you can, and be safe when you can’t. Also, maintain communication with the ones you love. Don’t take for granted the time you get to spend with them because tomorrow’s not promised.